Help Me, I Need a New Hobby

Improper ways of finding hobbies and paying strangers to be your friends

At times, I needed a new hobby. The old ones ran their course. Some became too dangerous — I gave up soccer after a broken nose, a rib, and a toe. Others were ejected from life by circumstances — can’t whitewater kayak on the Midwestern plains. A few were banned by past partners for their ruinous impact on the relationship — adventure racing took too much time away from our arguing, and chess turned me into a pedantic bore philosophizing on how life imitates chess. Sorry about that one.

So when the hobby runs its course, I must find another. I did not believe I had a method for picking them, but, over four beers, a friend outlined the criteria I subconsciously followed. The hobby must be complex enough to entirely take over my thinking to the detriment of important things. It must be ruinous to my finances. And it must be obscure enough for no one else but me and a small cohort of adherence to care. The last quality is important as it offers excellent opportunities to educate and enlighten innocents at parties. It is a good way to broaden your circle of acquaintances from your circle of friends.

By the early 2000s — that’s when this story takes place — I built a substantial list of past hobbies, which precipitated a crisis. Can I find something that fits the bill? Turns out, I did not have to look.

Around that time, at the beginning of the century, I moved to a small town of about twelve thousand people. It was a nice American suburb. Half, a bedroom community for people working in the capital but looking for affordable homes; half, locals who had never left; and a small part, seasonal migrants working at the tree nursery nearby. Nice town, with a functional main street, a few restaurants, a factory, and a festival celebrating Norwegian Syttende Mai — the independence day. And a bicycle store.

I saw it right away. Its name was the misspelled name of the town — Stoughton, but phonetically correct to highlight the oddities of the local accent — Stoton Cycle. It shared the signage with the coffee shop but had its own space for the slogan: “If it’s in stock, we’ve got it.”

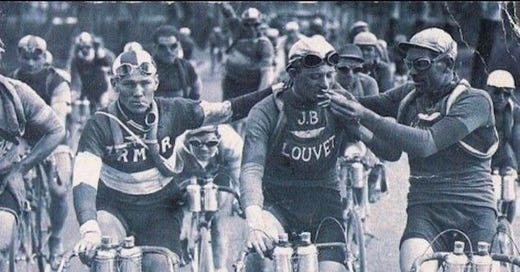

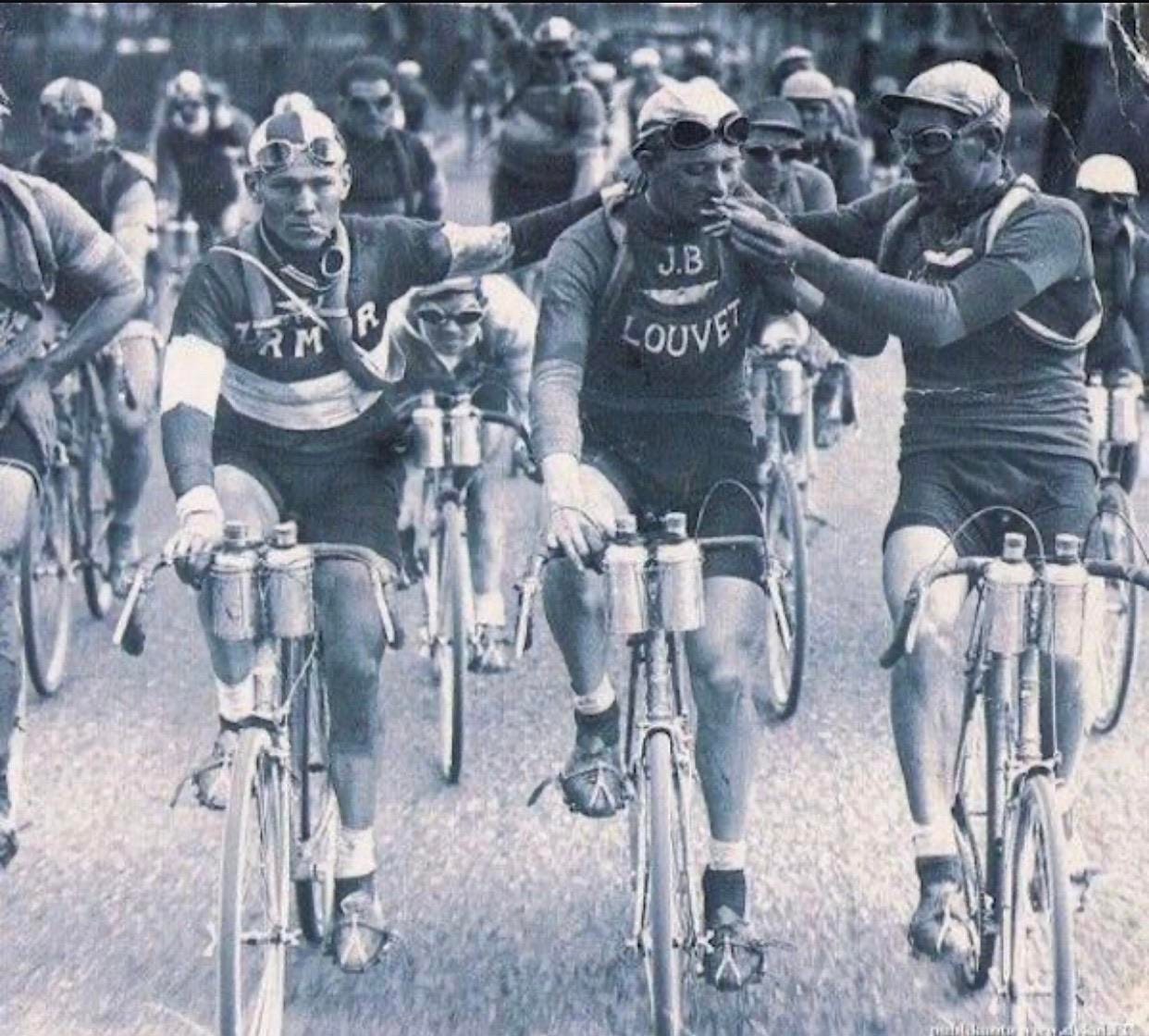

The store was in the basement but had high windows to let in the light. Rows of bikes and accessories. Old posters of racers climbing the French Pyrenees and smoking cigarettes on their bikes. New posters of modern racers covered in the logos of their sponsors but healthy-looking in contrast.

The stereo played local talk radio. The station was left-leaning, but this particular show espoused an especially far-left ideology that I saw not working during my childhood in the communist Soviet Union.

The only man in the store was in a black apron, turning wrenches in the back. “Can I help you?”

“No, not really.”

“Huh.”

He went back to unscrewing the peddles. I stood in the middle and looked at bikes from a distance. The prices looked right, triple what I should spend. The helmets were expensive, too, as was the clothing kit.

“A lot of people race bikes around here?” I asked.

“Just ride them. A few.”

“But some race?”

“Some.”

“I think I would like that.”

“What?”

“Racing.”

“Why?

“Seems fun.”

“Aha. No, not a lot.” He shook his head.

“What? Not a lot of fun?”

“A lot of fun. Not a lot race.”

“That’s good.”

“Why?”

“Easier to win.”

He set down his wrench, turned around, and sized me up the way a boxer would before a bout. He was taller than me, with an Italian face, like the smoking men on the posters. His hands were covered in grease. He could give me a beating, I suppose. It would certainly ruin my light shirt. So, I opted for de-escalation.

“Who is the communist around here?”

He sized me up again, with a more obvious intention. I could sense his annoyance and confusion. But then he laughed, walked over to the radio, and turned it up.

“No,” he said, “I listen for the conspiracy theories, deep state and inside jobs, and all.”

“Yeah, reasonable,” I said, “maybe I’ll stay awhile and learn something.”

He sized me up again. “Do you have a bike?”

“No, why?”

“To race.”

“Yes, yes. No, I don’t.”

“So you need one?

“Does not look like you have any racing bicycles,” I say.

He waves his hand around the store.

I shake my head, “I want the one where you can see the carbon fiber, like on those bikes in the Tour de France.”

His face lit up. I could see he appreciated my enthusiasm for good equipment. He dropped a catalog in front of me, opened it up, and pointed to a thing of beauty. I saw the price and considered that his enthusiasm was about the commission.

We chatted about bikes, discussed my goals, discussed my budget, then leafed a few pages back to a more modest section. I looked at the bikes and the prices. We leafed a few more pages back, then a few more. Finally, we found a match between the prices and how much beautiful carbon fiber I could see — a sliver on a top tube. I began to haggle over the price. He closed the catalog, threw it atop the toolbox, turned up the radio, and went back to wrenching the peddle.

“Maybe I could talk to the owner?” I yelled over the noise. He pointed at himself. I nodded and gave him the thumbs up. “Ok, good on the price.”

He turned the radio down. “It will take a couple of weeks to get the bike.”

“Okay.”

Every few days, I stopped by the store, and he would remind me, “A couple of weeks.” A couple of weeks later, it was still “a couple of weeks — component supply crunch.” In two more weeks “strike in Italy — no derailleurs for the rear wheels.” Two weeks after that — “wheels are back-ordered.”

I would stop, and we’d chat about bicycling and life, the crazy things happening in the world, and the lunatics running some countries. With each visit, I noticed a lessened annoyance and a softening edge to his demeanor. And by the end of the second month of “supply chain disruptions,” I almost thought he was glad to see me. But then, I thought it was a kindness afforded a newcomer to his town who needed a friend.

When the bike finally made it into the shop in a large cardboard box, and I watched him put it together as we drank beer, I saw the care he took in assembly, a care you afford a friend. I looked at the time on the clock — he was working after hours. I felt thankful a person would grant me a favor of their company, and I now regretted calling him a communist.

For the next twenty years, the bike shop owner Phil and I, and many of our cycling friends, clocked tens of thousands of miles around the southern parts of Wisconsin. I stopped at his store each week. We sipped beers and talked about the going-ons in the sport. I’d tell him about bicycle crashes I’ve seen. He’d tell me about some fellow trying to buy a bike he did not know much about, and, without irony, I would make fun of a poor schmuck.

It turns out, you can pay someone to become a lifelong friend. But Phil paid back. Every couple of weeks, he’d join our backyard fires and always, always, brought quality beer. And good conspiracy stories that no one believed.

I raced. I never won any races but did well enough to advance through categories and race for cool teams. And my then-wife complained not once about that new hobby that stayed with me for two decades.

😂 this story had me laughing out loud from the title to the end!

That was a great read. Your description of the 'ideal hobby' fits coin collecting very well, a life burden I've taken on for 20 years now.