Tavan Bogd Uul, Altay - Surviving Where Three Countries Meet.

Essay. Learning to be happy in an expedition to the Altay plateau.

This story is from my younger days in Russia. That Russia is dead. Its replacement is run by a dictator and an oppressive regime of oligarchs. I am ashamed of the Russians who support it. And I am ashamed of the US politicians in my adopted country - the useful idiots and spineless Manchurian stooges who are rehabilitating Putin’s regime... But this story has little to do with politics. It is about discovery, and it is about people - who are not always synonymous with the country’s politics.

I slipped into the next stage of hypothermia. The shivering stopped and I no longer felt cold. How could it be? An hour ago, we baked under the relentless mountain sun on the Altay plateau. Now, I struggled to say a sentence. The cold rain and the rushing wind leached away my warmth, confused my thinking and ability to reason

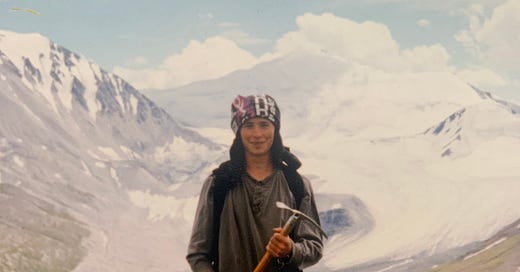

Author in the Altay Mountains in 1996.

My two comrades looked no better. James, the Canadian, was not shivering either. He sat with a stoned smile, gazed through me at the majestic glaciers - tall, beautiful, deadly. They descended from the Tavan Bogd Uul, the mountain that touched three countries at once, Russia to the North, Mongolia to the East, and China to the West.

Pavel looked sleepy. He was a researcher from Altay University in Barnaul, the capital of this south-western Siberian region. The city was a few hundred roadless miles away. Safe, unreachable, and never to be seen again. Not by us. Not by me. The wind drained my warmth and my future. And I was not even twenty.

The previous year, I studied in the United States. The amazing year was a lucky draw for a Russian kid in 1996. I returned to Barnaul for the summer. My English was good then, and that was how I ended up in the middle of nowhere, or maybe in the middle of everywhere, where three countries converged on a peak.

My dad’s friends were university researchers and every year, they drove military trucks into the vastness of the Altay mountains to do their research with a group of students. Twenty or forty people would pile into the back of the ZILs and into a dilapidated bus, then trek over “bezdorozhye” - the roadless high steppes - to the border of Altay. That particular summer, a Canadian planned to join them. He spoke no Russian, and the Russians spoke no English. So they talked to me.

“Egor, we need an English interpreter, unpaid but fed, to go with us to Tavan Bogd Uul,” Dmitry, the boss, told me. My father urged me to see him. Dmitry sat in a peeling wooden chair in a dilapidated station that hosted their equipment and their weekend parties.

“To where?” I said.

“Tavan Bogd Uul,” Dmitry walked to the map and landed his finger in the middle of the map, away from anything familiar.

“Yes.”

“Yes, what?”

“I am going.”

“Don’t you have any questions?”

“How many days?”

“Three weeks.”

“Yes”

Next week, I met James. The Canadian flew in from Alberta and moved into a hotel downtown for a week before our departure to the mountains. The hotel sat at the edge of a large Soviet square surrounded by classical government buildings, a fountain in the center, and the ubiquitous statue of Lenin in front. Everything in the dispiriting spirit of Le Corbusier.

I walked with James around the city and explained things: why people were crushing into buses instead of waiting for the next - no one had an idea when the next would come, maybe in ten minutes or two hours. I explained the workings of long queues - they looked like a mob, but everyone knew who they followed. I told him about the babushkas selling five-gallon buckets of strawberries - pensioners, pensions not enough to live on, so they were doing what they could to make it. I took him to an early Russian restaurant, and we both laughed at an attempt. He was a curious man and accepted knowledge with glee, his happiness the most foreign of qualities.

On the way back, he always stopped by a large Geiger counter display outside his hotel. He took a photo with his Leica of the number tallying the daily exposure to radiation. It was a vestige of the time when a nuclear fallout was the number one fear.

“Are people still afraid of that,” he asked.

“The nuclear war? No, they are afraid of the empty store shelves and missing out on butter when the store runs out before their turn in the queue.”

On the surface, he was what I imagined him to be: a typical Canadian with an amiable personality, pasty skin, and a soft midsection. But he was in South-Western Siberia seeking discomfort and adventure in the mountains where a few people had gone. He intrigued me. I grew up in this chaos, while he had willingly chosen it, if only for a time. To each his own, I thought. I appreciated his company, although sometimes felt ill at ease with his constant optimism. He was my window to the Western world. I sampled it the previous year and craved to return to it.

At the end of the week, we mounted ZIL military trucks and an old bus. About thirty of us split between the three. People on the bus had the seats, and we in the trucks lay on sleeping bags and provisions. We drove twelve hours to the end of the paved Choysky Tract deep in the Altay Mountains, then followed gravel roads deeper still. We came to a steep ridge, where the gravel withered into a dirt and climbed into the clouds.

We disembarked and walked ahead of the vehicles. They crept behind us up the craggy slope. We marched out of the cloud, and each of us stopped in awe upon reaching the crest. The high-altitude plateau extended past the horizon, framed by the glaciated peaks on each side. Vast expanse, barren of people and roads. Only the green of grasses, the gray of rocks, and the bluish patches of ancient lichen blended in the distance and ran against the white of the snow.

We still had two days to drive. Endless bouncing, endless singing, endless arguing, endless laughter, endless translation of questions from Russian to English and back. It was exhausting, but I relished my role. I was a conduit of information from the recently forbidden West.

We arrived to the end of the plateau and build a camp of four tents. Two for sleeping, one as a lab, and the fourth as a mess hall. Then, people went to work.

A team collected samples of flora. Another sampled the rate of photosynthesis at various altitudes on the slopes. Geologists collected rocks. Drivers chased wild horses - oversized ponies, more like it - to keep from boredom.

I followed James, who followed the botanists. He collected tiny flowers, purple or white, to take back to the camp and study them through a magnifying glass, then press them between sheets of paper. In the evenings, people gathered around the fire with two guitars and thirty voices.

My translation duties began to grind on me. I could not join the easy fun around the fire; always caught between questions, a medium, and never a person. James noticed my growing resentment and understood.

Tomorrow, he said, we should rest from the Russians. Maybe explore the approaches to Tavan Bogd Uul? See if we can hike around it? Imagine, he said, we could walk through three countries by hiking around one peak! Hike it? It would be mountaineering, I told him. He shrugged. But I liked the idea.

After breakfast the next day, we left for the mountain. Pavel insisted on tagging along. He spoke broken English and addressed James directly, so I did not mind.

We hiked through the tundra. We walked on the grass around the granite patches, away from the thin layer of lichen on the rocks. Up here, the lichen took centuries to cover rock, and a careless step wiped out decades of growth.

We reached the glacier in two hours. James looked at the ice and the terraced pitch. He shook his head.

“No, I am too fat. You climb it. I’ll be right here.”

He plopped on the ground and leaned against the rock. He pulled a notepad from his back pocket, rummaged for a pen. “Go, go.”

Pavel and I went on. Easy climb at first, then steeper, the mountain forcing us to drive our ice axes into the snow and soft ice, to take cautious steps. By eleven thousand feet, the ice hardened and bounced our axes away from the ancient surface with a thunk. We slowed. I looked behind at a distance we covered, also a distance we could fall.

Pavel missed a strike and slipped. He slid past me and continued for another ten yards. He dug the spike of his axe into the snow and arrested his glide. He looked at me, eyes wide with fear.

“We should keep going, shouldn’t we?” He asked.

“I think so,” I said in a shaking voice.

“You sure?”

“Yeah. Right?”

Pavel climbed back to me. He sat down. Swallowed. Drove the edge of his axe into the icy slope and held on to it with both hands. His legs twitched. He looked down and swallowed again.

“Yeah, we keep climbing. Right?”

“We should.”

We sat without looking at each other. The valley ran away from us to a distant range jutting above the horizon. We came from there, a two-day drive away. I wanted to be on the other side, on the road or in a village where glaciers were not welcome.

“Is he waving?” Pavel pointed to a dot below. It moved in a Brownian motion, up and down and randomly sideways.

“Right?”

“A problem? I think there is a problem.”

“Go down to see what’s up?”

We glissaded, a controlled slide to a stop with the axe. Lift the axe to releases, glide down over ice pressing the axe into it to slow the descent. Stop to rest. Repeat. Butts wet from the ice, hands shaking from effort and fear. Exhilarated. Two thousand feet of risky fun.

We stepped of off the glacier onto the rocky plateau. Without the ice underneath, the air felt hot. That’s how it was up here. Cold ice and hot rocks, freezing nights and hot days, if the wind did not blow. Scorching at noon.

James lay on the ground. We rushed to him.

“James,” I yelled.

He snored. I shook him awake.

“Why were you waving?” Pavel asked.

“Waving? I was not.”

“We saw you waving,” I said.

He shook his head, “Did you make it to the top?”

“We thought you needed help. We came back.”

“I was sleeping.”

We ate lunch in direct sunlight. There was no cover for miles around, and the sun burned my skin through the shirt. My head sweated underneath the long sleeve that I tied around it to keep away the punishing rays. I looked back at the glacier and marveled at the contrast between the cold ice and the hot rock just meters away. A very Russian scene, cold and hot in proximity, the richness of spirit and poverty of life under the same house roof, the beauty of creativity, and the ugliness of oppression under one nation.

“Yikes,” James said. Pavel and I looked behind us. A dark cloud crept over Tavan Bogd Uul. Ugly with anger and impatience to drop the heavy rain, lightning, and thunder. A storm like this passed two days ago when everyone was still at camp. A fury. Loud, angry fury throwing lighting bolts into rocks, burning divots in granite, and filling them with hissing water. Ready to burn anyone in the open.

We tossed sandwiches into our backpacks.

Pavel led our dash, half walking, half running. I followed. James huffed behind me. But we had no chance. The towering colossus rushed upon us.

Pavel pointed to three rocks, each four feet tall and leaning on each other. It was an imperfect shelter but the only cover above ground. We swerved and crashed behind them. We breathed heavily from the effort, from the heat and anticipation of a beating.

The next two minutes were calm. The sky darkened. The heat shifted to cool. A breeze arrived from the ridge, carrying cold and a warning. Noise. The noise of a pounding rain or hail. Vicious, angry, without empathy.

It hit with force. The frigid gusts and the sheets of rain attacked our exposed skin. The force of the wind tore at my eyes. It blew the shirt off my head and launched it beyond the crest of the ridge. Pointless to chase it.

I wiped off the tears and turned away from the blast, then glanced at my companions. In their eyes, the excitement surrendered to fear. The same fear infiltrated my body.

I looked North in the direction of our camp. The horizontal sheets of rain erased all around us and confined us to a tiny space of mere feet where we could see nothing but the rock vanishing into the storm. The rain soaked our clothes, and the wind peeled away the moisture. It cooled our bodies with frighting speed and within minutes we were shivering from growing cold.

“Should we move?” Pavel asked, eyes wide with fear, arms shaking.

“No, wait it out behind these rocks,” James said.

“They aren’t doing much.”

“Will walk in circles in this rain,” James argued.

“Keep the wind at your back.”

“In the mountains, it circles.”

We stayed. Shivered. Listened for the thunder. But we heard none. A lucky break. My frantic thoughts raced through our options and what was to be. But slowly, they settled into a strange calm. And my body slowed its shaking, and the cold receded. My body ignored the rain and the wind and began to feel warm. Content. I heard my thoughts broadcast to me from a distance. ‘Advancing hypothermia, man!’ but the thoughts carried little meaning, like a passing billboard on a highway after hours of driving.

The deluge stopped, and I watched with disinterest the sheets of rain departing in the wind. The curtains opened on the mountains again, and James gawked in amazement as if seeing them for the first time. I watched him watch the mountains, and I listened to the distant broadcast of my thoughts, which did not seem my own. ‘Silly man James, excited about everything. Silly optimism. Watching the Geiger counter! Taking photos. Who cares? Only people who never worry about the basics of life, of food. Only people who don’t understand queueing for bread. These mountains will teach him. This country will teach him. The weight of its sad history will turn him into a cynic as it did all of us who had the misfortune to be born in this Soviet paradise. So what? He won’t make it out of here, and I will not have to translate. That’s nice. What a goof!’ The thought arrived in small packets of short phrases. They imprinted themselves in my mind without making sense then.

The wind followed the departing rain. The mountains sighed with the last puff and relieved us of torment.

We sat there. Stupefied. Defeated. Incapable of movement in our hypothermic sloth. Incapable of the only rational decision to move and awaken the muscles through a force of will and re-ignite the furnace of life. But the mountains took pity, partied the sky, and flooded the valley with sunlight. The sun’s warmth touched our bodies. At first, we ignored it as we ignored the cold, but it thawed the skin and the reluctant muscles, raised the temperature of our bodies. We began to shake. The shaking awakened our reason, and we understood the gift. The mountains let us keep up our future. Walk home, they said, you feeble men.

We shook from the sloth and ambled along the ridge in silence. Unsteadily, but then with surety as our shaking stopped. A kilometer, then another, then towards the tents, into the safety of our camp.

In the evening, we heard of others caught in the same distress. All of us made it back. All of us retold our stories with extreme brevity and with a fatalistic shrug. But not the Canadian James. He seemed happy to walk out of the predicament. I watched him eat his food, and I envied his hunger. Yes, hunger for food, and his hunger for life, for experience. I envied his zeal to be happy. His zeal to smile and his silly drive to make others laugh. Superfluous things, I thought. Was he a fake?

I ate my hot soup, chewed the tough pieces of chicken floating in the broth. It warmed me on the inside, mellowed my edge. Why am I set against him, I thought. I felt guilt, then affection. Could he be just a kind man?

“Why are you always happy,” I asked him with a restrained resentment in my voice.

“It’s a choice,” he said.

“That simple?”

“No, it takes the hardest of thinking.”

“Yeah? Just thinking?”

“No, you also need to live through the hardest of things.”

I looked at him and was about to scoff. What would a wealthy Canadian know about the hardest of things? But his smile turned hollow, and in his eyes, I saw a glimpse of a personal history that could fatally wound. Were the hardest things beyond the circumstances of daily struggle? I restrained my scoff. I inhaled to ask what had happened to him, but he pre-empted me with the widest, most sincere smile. “We all will have something to teach us.”

I do not know what happened to him before, nor do I know what happened to him since. We did not stay in touch. But in the following decades, I understood the truth of his words. Life is unsparing with its difficult gifts. When it hits, we make choices. The strongest choose a path to happiness.

I need to reread this tomorrow. We fled Czechoslovakia in 1968 after the Russians invaded. I was 7. It was old enough to be inoculated with a generous dose of distrust towards the happy north American (i am a Canadian now). I felt in my bones your inner dialogue towards James. And I am now old enough to know the wisdom of James' hard choices to be happy. Thank you for this.

Egor ...what a life you have led! Thanks for sharing both the adventure and the layered lessons. Very well done. J